Mr. Schneider, DB Cargo is using 13 million liters of HVO for its locomotives in Germany this year. How easy is that?

Jörg Schneider: Quite simply: Where HVO is available, we refuel with HVO. Where it is not, we use fossil diesel. Our locomotives are designed to run on HVO and fossil diesel in any mixture ratio. In 2026, we will break the 50 percent mark in Germany. Then our locomotives will refuel with just as much fossil diesel as HVO. Internationally, we are not yet that far along everywhere. In northern Italy, thanks to political support, all our trains already run on HVO. In Eastern Europe, on the other hand, it often fails due to availability and bureaucracy.

Dr. Toedter, HVO is often referred to as a "bridge technology." Are we underestimating its long-term significance?

Dr. Olaf Toedter: Absolutely! HVO is currently the most climate-friendly solution we have. We are reducing CO₂ emissions by around 90 percent. As long as there is no better alternative in sight – and I don't see one in the next ten years or so – HVO is the technology. Period. It is not a transition, but a real solution.

Jörg Schneider: I would add that it is only thanks to HVO that we are meeting our climate targets today. But honestly, HVO does not solve the problem of local emissions — CO₂ and nitrogen oxides are still produced, albeit significantly less. If the requirements become stricter — for example, for local emissions in cities — we would have to reassess. But currently, there is no better option for freight transport. If HVO did not exist, we would have to leave our diesel locomotives idle.

Dr. Toedter, you say that the combustion engine is not the climate problem, but rather fossil fuels. Why is that?

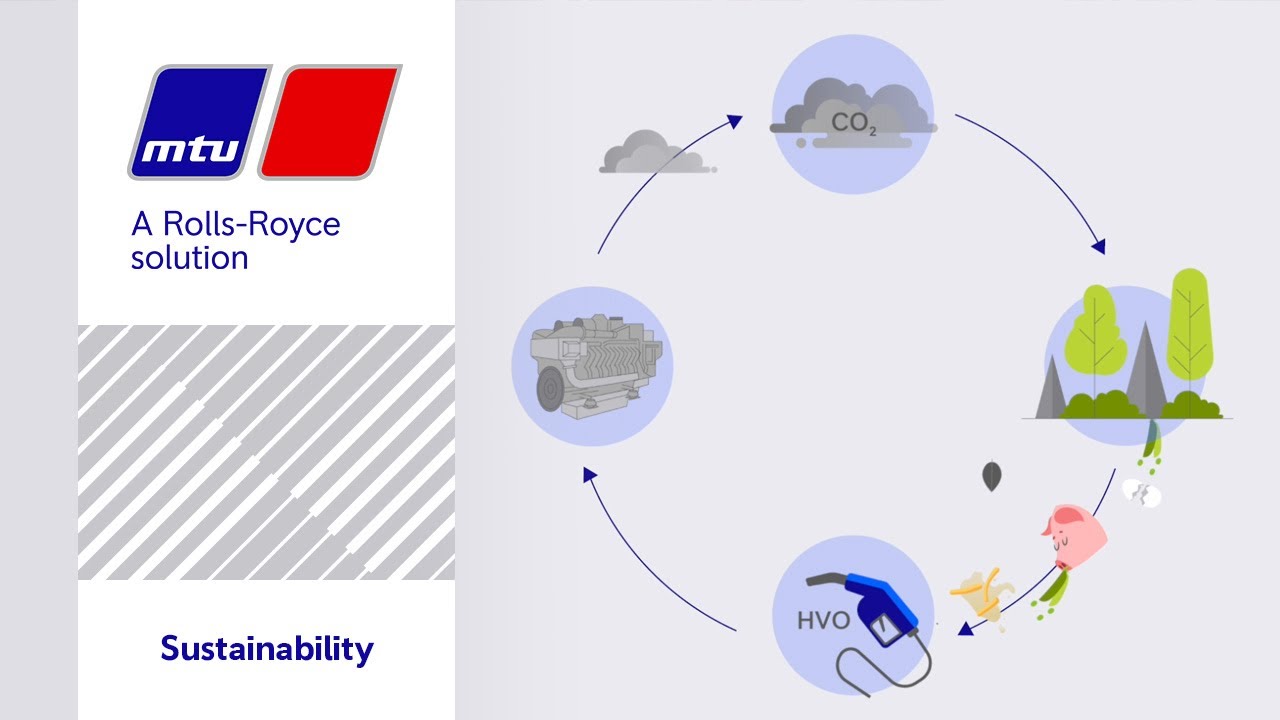

Dr. Toedter: Quite simply, with fossil diesel, we extract carbon from the ground and emit it into the air as CO₂. With HVO or eFuels, we use carbon that is already in the atmosphere — for example, from waste or through power-to-X processes. The cycle is closed, and the balance is much better. The engine itself is only a converter. The problem is the energy source.

Dr. Toedter, you say that CO ₂ remains in the atmosphere for around 100 years. Why does that make the situation so urgent?

Dr. Olaf Toedter: Because we no longer have the time to wait. Every kilogram of CO₂ we emit today pollutes the atmosphere for a century. If we want to achieve the 1.5-degree target, we have to reduce emissions immediately – not in ten or twenty years. The later we start, the more radical the measures will have to be. And radical measures mean economic and social upheaval. With rail, it's not about perfectionism, it's about speed. HVO and eFuels are available today – so why not use what works? Every year of discussion costs us options. Physics doesn't wait for compromises.

Jörg Schneider: That's exactly what we're seeing at DB Cargo. Some of our customers – from the chemical to the automotive industry – have set themselves very ambitious climate neutrality targets for 2035 or 2040. They won't achieve them if we don't convert our logistics chains within the next ten years. With HVO, we are already reducing CO₂ emissions by around 90 percent compared to fossil diesel. This is not a theoretical scenario, but a reality. The question is not whether we will switch, but how quickly we can adapt the infrastructure and use HVO in the long term under economic conditions.

Can we all switch over without any problems?

Dr. Toedter: Are you referring to the availability of raw materials? No problem. The US Department of Agriculture shows that HVO production can be ramped up. But we need reliable certifications. If a supplier claims that its HVO comes from certified waste, that has to be true. Otherwise, we're buying a pig in a poke. The EU rules are in place – they're just not being consistently implemented.

Jörg Schneider: In northern Italy, we have already succeeded in switching to HVO, as politicians have created price parity with fossil diesel through tax breaks. In Eastern Europe, there is a lack of suppliers and filling stations. This is not a technical problem, but a regulatory one.